What Do We Mean by Transition?

Within the EU’s strategic and regulatory framework, the transition refers to the profound transformation of the economic system required to achieve climate neutrality, while safeguarding long-term industrial competitiveness. It involves decarbonising energy systems, industrial processes, transport, agriculture, and buildings, as well as reorienting finance and innovation towards sustainable outcomes.

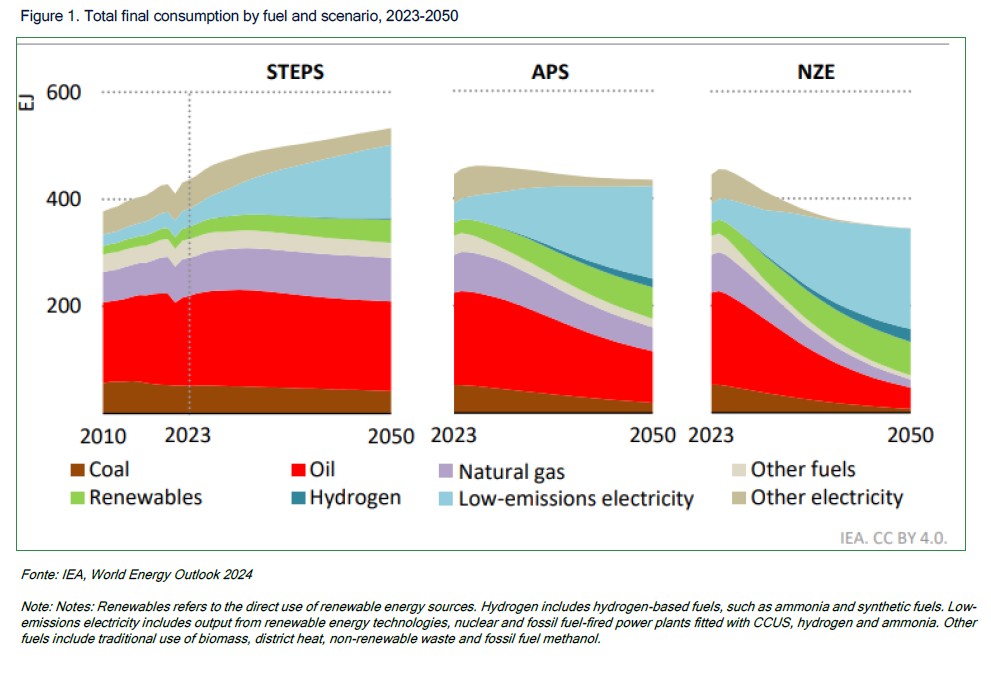

This shift is framed within the EU Climate Law *1 (References below), which sets the objective of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 and a binding intermediate reduction of 55% by 2030, compared to 1990 levels. As shown in figure 1, the share of fossil fuels in final energy consumption declines across all climate scenarios this decade, dropping from 66% today to 55% in 2050 in the STEPS scenario, with even faster reductions projected in other scenarios.

Transition is neither linear nor automatic. It demands coordinated efforts among governments, industries, financial markets, and civil society. This process involves regulatory reforms, realignment of corporate strategies, reallocation of capital, and workforce adaptation. Fundamentally, the transition redefines value creation by internalising environmental constraints and social considerations within financial and industrial decision-making.

Transition as a Lever of Competitiveness

The European Commission has framed the transition not as a constraint, but as a catalyst for a new era of economic competitiveness.

This strategic pivot echoes the three pillars outlined in the April 2024 Draghi Report (*2) on the future of European competitiveness – security, innovation, and decarbonisation – which together define a new industrial policy framework.

Transition planning is no longer an environmental issue alone, but a core component of Europe’s long-term resilience and strategic autonomy. The twin initiatives – the EU Competitiveness Compass (*3) and the Clean Industrial Deal (*4) – launched between late 2023 and early 2024, articulate a forward-looking policy agenda that aligns climate ambition with industrial policy.

The EU Competitiveness Compass identifies key structural drivers of competitiveness in a climate-constrained world: clean energy affordability, skilled labour availability, access to critical raw materials, and financing for green innovation. The Clean Industrial Deal complements this by providing transition pathways and support mechanisms for carbon-intensive sectors such as steel, cement, chemicals, and transport.

These initiatives signal a broader policy pivot: from target-setting to implementation. The goal is to establish a regulatory environment that incentivises proactive transition strategies and penalises inaction. Transition plans (*5), once voluntary, are increasingly becoming a prerequisite for accessing public funding, securing market share, and attracting long-term capital.

Recent international commitments further reinforce this momentum. At COP29 (*6) in December 2024, countries committed to tripling global renewable energy capacity and doubling energy efficiency improvements by 2030. Achieving these targets will require substantial capital mobilisation and close alignment across policy, finance, and industrial ecosystems.

Policy and Regulatory Drivers

The EU has built an interconnected regulatory architecture to embed transition planning and performance into corporate governance and financial reporting. This includes:

- Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD): In force from January 2024, it requires large companies and listed SMEs to report on sustainability matters, including detailed transition plans, under the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS). ESRS E1 requires companies to disclose GHG emission targets, progress on decarbonisation, and CapEx alignment.

- Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD): Provisionally agreed in 2024, it requires companies to adopt transition plans aligned with the Paris Agreement, integrating them into corporate strategy and board accountability. It introduces binding due diligence obligations and risk mitigation measures along the value chain.

- EU Taxonomy Regulation: Establishes criteria for economic activities to be considered environmentally sustainable. While initial focus was on mitigation and adaptation, the Platform on Sustainable Finance is expanding coverage to include transitional activities and social taxonomy criteria.

- Omnibus Regulation I (2024): Introduces proportionality mechanisms to support SMEs’ compliance with CSRD and allows phased application of sector-specific transition disclosures.

This regulatory infrastructure positions transition planning as a core component of corporate strategy and a key determinant of access to financial markets. It also fosters comparability, reduces greenwashing risk, and aligns capital allocation with long-term EU climate objectives.

Investment Needs and Financial Flows

Achieving the EU’s climate and industrial objectives will require capital mobilisation on an unprecedented scale. The European Commission estimates that between €600–700 billion annually must be invested to meet Fit-for-55 and REPowerEU goals (*7). This includes substantial allocations for energy systems, transport electrification, industrial decarbonisation, and building renovations.

According to the IEA, in 2024 over 700 GW of new renewable capacity was installed globally, bringing the total renewable share of electricity generation to 32%. Despite this progress, a substantial gap remains between current investment levels and those required to meet climate targets. Bridging this gap requires the coordinated deployment of public financing instruments, such as the Innovation Fund and InvestEU, as well as the activation of private capital through blended finance structures, guarantees, and green bond markets.

Expanding access to finance for SMEs and hard-to-abate sectors remains a critical challenge. Clear taxonomies, credible transition plans, and de-risking mechanisms will play a decisive role in accelerating investment flows into climate-aligned activities.

The Role of the Financial Sector

Financial markets are pivotal in accelerating transition. Institutional investors, asset managers, and financial analysts are increasingly expected to assess the credibility of transition plans, identify misalignment risks, and engage with issuers to promote progress.

This requires moving beyond backward-looking ESG scores towards forward-looking transition assessments. Key elements include:

Verifying alignment with science-based targets (e.g. SBTi) (*8).

- Analysing CapEx trajectories and technology adoption curves

- Assessing physical and transition risks through scenario analysis (*9).

- Integrating policy scenarios, such as the IEA Net Zero or EU 2040 framework, into valuation models (*10)

The financial profession must also enhance its skills base. Mastery of sector-specific decarbonisation pathways, interpretation of regulatory disclosures, and integration of non-financial KPIs with credit and equity metrics are increasingly essential competencies.

Moreover, the transition requires reskilling the workforce and expanding the expertise of ESG professionals, risk officers, and corporate strategists. Financial institutions must invest in capacity building to integrate sustainability into mainstream investment analysis and product design.

Assessing the Credibility of Corporate Transition Plans

An investor should focus on several key points to assess the credibility of a transition plan (*11).

- Firstly, examining the governance structure is crucial to identify issuers that truly integrate climate into strategic management. The investors should ensure that transition efforts are prioritized at the highest organizational level, with dedicated committees or tools like shadow carbon pricing, etc.

- Next, attention must be paid to the targets set for emission reductions. Investors should evaluate the level of ambition and whether these targets cover all relevant areas of the organization’s operations. It’s important to check the scenario or framework used to verify alignment with international climate strategies. Are they consistent with global standards?

- Participation in initiatives like the Science Based Targets Initiative can provide additional credibility to these goals.

- Understanding how the company plans to achieve these objectives is also essential. This involves probing into the resources allocated towards the transition, including dedicated capital expenditures (capex) aligned with European taxonomy.

- Evaluating historical performance and the achievement of previous carbon targets will give insights into the organization’s reliability. Moreover, the monitoring of controversies or any instances of greenwashing is important; this ensures that the organization’s claims are genuine and not merely a façade for maintaining a positive public image.

Social and Workforce Dimension of Transition

An effective transition must also be just and inclusive. Tackling energy poverty, regional disparities, and the distributional impacts of decarbonisation policies is essential to sustaining public trust and ensuring political stability.

This entails integrating social safeguards into transition plans, supporting communities reliant on high-carbon sectors, and aligning investments with job creation and reskilling initiatives. Financial institutions and analysts should incorporate social impact considerations into their evaluation frameworks, recognising that sustainable competitiveness requires cohesive economic and social systems.

Conclusion

Transition and competitiveness are no longer parallel goals but mutually reinforcing imperatives. The EU’s evolving framework recognises that long-term economic strength depends on timely, credible, and well-financed transition strategies.

Ensuring a credible and actionable transition pathway requires not only regulatory clarity but also strong alignment across industry-led initiatives. The current uncertainties surrounding Net Zero alliances, including those representing asset owners (NZAOA), asset managers (NZAM), banks (NZBA), and data providers (NZDPU), may slow the pace of convergence on key methodological frameworks. Many European financial institutions rely on these alliances for guidance in setting science-based targets and interim milestones toward 2040 and 2050. However, rather than undermining progress, this moment reinforces the need for sustained engagement and coordination. Working together across regulatory and voluntary frameworks enables the financial sector to maintain ambition while addressing the complexity and realism of transition timeframes, as reflected in both legislation and market practice. In this context, accelerating the review and implementation process of key regulatory instruments, such as the Omnibus Regulation and the revision of the SFDR is essential. Timely, coherent updates to the EU sustainable finance framework will allow investors to navigate transition challenges with greater clarity and confidence.

EFFAS and its ESG Commission remain committed to supporting this evolution through technical insight, professional training, and constructive dialogue with institutions and standard-setters at both European and international levels.

EFFAS reaffirms its commitment to supporting the financial community through analysis, training, and thought leadership. This Position Note contributes to that effort by elucidating how climate ambition translates into industrial opportunity and financial responsibility. By equipping financial professionals with the tools to understand and respond to transition dynamics, EFFAS fosters a more transparent, efficient, and impactful allocation of capital – aligned with the shared goal of a competitive, climate-neutral European economy.

For more detailed information visit the official pages on the European Commission’s website.

—————————————-

The EFFAS CESG was established in October 2007 to facilitate the integration of ESG factors into investment processes. Composed of investment professionals from leading European and global sell-side and buy-side firms, including fund managers, financial analysts, and equity specialists, the CESG has been mandated by EFFAS to achieve several objectives. These include establishing and coordinating EFFAS’s position on ESG reporting, measurement, and valuation; consolidating ESG expertise among European investment professionals; extending ESG efforts beyond individual EFFAS member companies; engaging in policy, academic and industry initiatives on ESG issues; organizing European-level conferences on ESG issues; and representing EFFAS in international conferences and projects related to ESG issues. CESG serves as a reference and networking Centre for ESG integration efforts of investment professionals across Europe.

https://effas.com/commissions/effas-commission-environment-social-and-governance-cesg/

About EFFAS

EFFAS is a Not-for-profit organisation set up in 1962 with 15 national member associations in Europe, representing more than 18,000 Financial analysts, Asset managers, pension fund managers, corporate finance specialists, risk managers, treasurers among many other professional profiles from the investment profession. EFFAS is a certification body for finance with over 27,000 certificate holders worldwide.

For any further information, please contact:

Álvaro Wagener Díez | Marketing & Communications Manager

E-mail: a.wagener@effas.com | Phone Number: +49 69 98959519

References

1 EC, Reg (EU) 2021/1119 – EU Climate Law, 2021, https://tinyurl.com/2yjjah3e, Last access 16.03.2025.

2 EC, The Draghi Report – A competitiveness strategy for Europe, 2025, https://tinyurl.com/y4p74dd5, Last access 20.07.2025.

3 EC, COM (2025) 30 – EU Competitiveness Compass, 2025, https://tinyurl.com/bdzmc4ar, Last access 17.03.2025.

4 EC, COM (2025) 85 – EU Clean Industrial Deal, 2025, https://tinyurl.com/2uy7zmc3, Last access 17.03.2025.

5 CSDDD Art. 22: Requirement to adopt and implement climate mitigation transition plans compatible with the Paris Agreement, with targets in 5-year steps from 2030 to 2050. The European ESRS E1 standard, as envisaged by the CSRD, has a unique aspect: companies are required to communicate a detailed plan outlining how their strategy and business model is compatible with the transition to a sustainable economy. The plan must demonstrate the company’s commitment to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions progressively to achieve climate neutrality by 2050, in line with EU targets.

6 Specifically, 58 countries have pledged to increase global energy storage capacity six-fold over 2022 levels, with the goal of reaching a total of 1,500 GW by 2030. COP29, Global Energy Storage and Grids Pledge, 2024, https://tinyurl.com/2d42purm, Last access 16.03.2025.

7 ECB, Europe’s tragedy of the horizon: the green transition and the role of the ECB, Mag 2024, https://tinyurl.com/4xyk3awd, Last access 16.03.2025.

8 In the absence of a binding regulatory framework, the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) has emerged in recent years as a reference point for the development of decarbonisation pathways, both general and sector-specific, developed on the basis of scientific data, scenario analyses and sustainability principles. Among the various sustainability principles, SBTi follows those defined by the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals), the Paris Agreement, the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) and the GHG Protocol (Greenhouse Gas Protocol). Furthermore, it is based on the Corporate Net-Zero Standard, the recommendations of the TCFD (Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures), the Just Transition Principles and the Planetary Boundaries Framework.

9 NGFS, Overview of Environmental Risk Analysis by Financial Institutions, 2020.

10 IPCC, Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C (SR15), 2018 and IEA, Net-Zero Roadmap (NZE), 2021.

11 To support consistent and structured assessments, investors are encouraged to refer to emerging technical frameworks that consolidate best practices for evaluating the credibility of transition plans, such as the one developed by the World Benchmarking Alliance (WBA) and the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment. WBA & CCSI, Assessing the Credibility of a Company’s Transition Plan: Framework and Guidance, 2024, https://tinyurl.com/kexbf8td, Last access 20.07.2025.